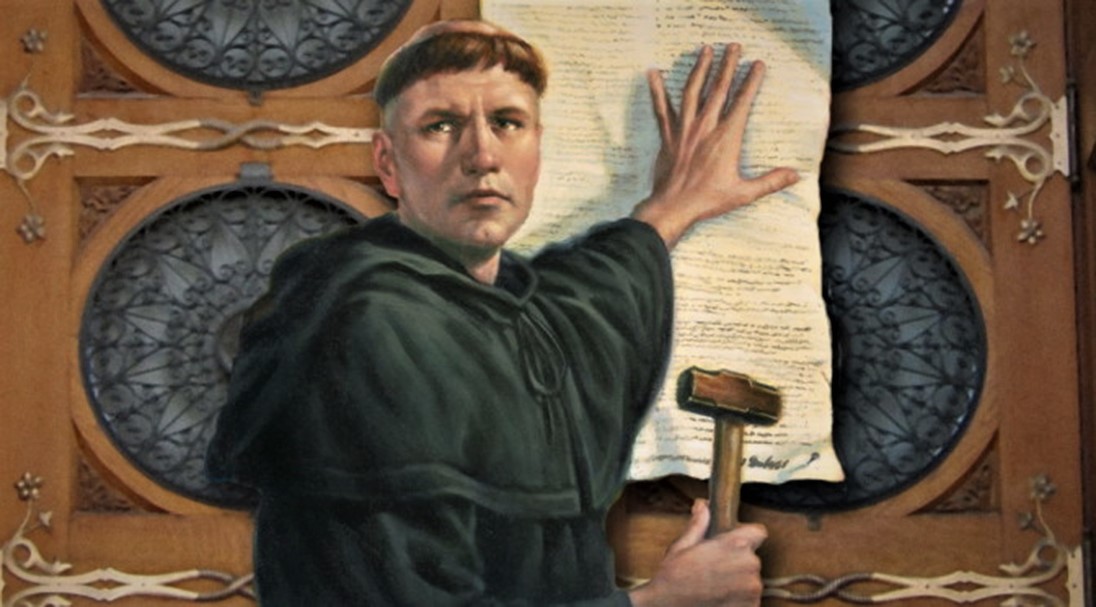

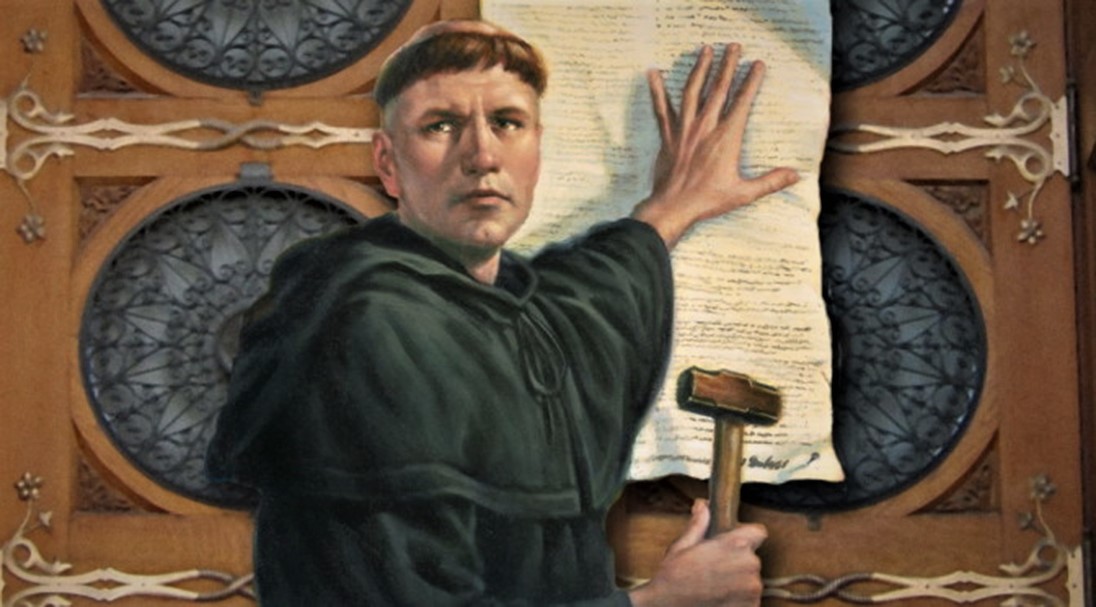

This coming October 31st marks the five hundred year anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. On October 31, 1517 Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in Germany. These 95 Theses became the foundation of the Protestant Reformation, which for many restored the biblical ideal of justification by faith and thereby the purity of the Gospel message.

This coming October 31st marks the five hundred year anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. On October 31, 1517 Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in Germany. These 95 Theses became the foundation of the Protestant Reformation, which for many restored the biblical ideal of justification by faith and thereby the purity of the Gospel message.

Earlier in 1517, a friar by the name of Johann Tetzel began selling indulgences in Germany as a mean to raise funds for the renovation of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. By purchasing an indulgence, one could gain the release of a sinner from purgatory or help ensure one’s own salvation. For example, if someone suspected that Uncle Joe was not quite ready for heaven when he died, dropping several coins into the box carried around by Tetzel would remedy that situation by instantly delivering Uncle Joe from purgatory into heaven.

Luther condemned this practice of indulgences, the subject of several of his 95 Theses. It’s easy to see why he objected to such manipulation of the people.

Justification by Grace Along with Works

In the Roman Catholic Church of Luther’s day, justification had become a lifelong process through which one received grace through the church and its sacraments that enabled him or her to do the good works necessary for salvation.

Can you see how such teaching would create much uncertainty regarding one’s final status before God? How could anyone know if they had been faithful enough in avoiding sins so that God would pronounce them righteous or justified at the end of their life?

The priests of Luther's day must have dreaded seeing him walk into their confessional booths.

This is why young Luther spent hours at a time confessing his sins to a priest. He believed that getting into heaven that he confess all his sins and live as good a life as possible. As a result, he meticulously and fervently confessed everything he thought might even possibly be a sin. The priests of Luther's day must have dreaded seeing him walk into their confessional booths.

Justification by Faith Alone

As Luther studied Scripture, he realized that God did not base our salvation on a combination of grace and personal merit. He saw that our justification, or our righteous standing before God, did not result from a lifelong process of resisting sin and doing good works, but rather took place the moment we place our faith in Jesus.

The word the Apostle Paul used for justification denoted a judge in his day pronouncing a not guilty verdict upon the accused person standing before him. Sinners, like the person standing trial, are declared righteous once and for all time. It's not something that happens over time.

Justification takes place the instant we call out to the Lord in saving faith, not at the end of our lives. In Romans 5:1, Paul says “since we have been justified by faith, we have peace with God.” Our right relationship with God comes instantly; He declares us righteous the moment we believe.

The Apostle Paul often emphasized that God saves us totally by grace through faith apart from any merit of our own (see Titus 3:4-7 and Eph. 2:8-9). Good works come after our adoption into God's family, not before.

Luther based his revolutionary teaching at the time solely on Scripture. An allegorical interpretation of God’s Word had begun centuries earlier as a way for some to view Old Testament prophecy symbolically. As a result, those who interpreted the Bible in such a way viewed the Old Testament promises of a kingdom for Israel as something the church fulfilled spiritually.

Unfortunately, this allegorical way of understanding Scripture later eroded the purity of the Gospel as it opened the door for church tradition to contaminate biblical beliefs, especially those pertaining to salvation.

A Literal Interpretation of Scripture

Both Luther and John Calvin condemned such allegorical interpretations and the adding of human tradition to the teaching of Scripture. They brought their followers back to a literal way of interpreting God’s Word through two key principles.

The elevation of the Bible as supreme in all matters of faith became a key factor in restoring the sound scriptural teaching of justification by faith apart from good works.

The first such principle was that of “sola Scriptura.” This signifies that Scripture alone is our sole source and supreme authority when it comes to all matters pertaining to faith and practice. For the reformers, this meant that the Bible was sufficient for all spiritual matters and thus took precedence over all the traditions of the church and the teachings of all previous popes.

This elevation of the Bible as supreme in all matters of faith became a key factor in restoring the sound scriptural teaching of justification by faith apart from good works.

Secondly, Luther emphasized “Scripture interprets Scripture” as essential for interpreting the Bible. This precept stresses that all of Scripture is God’s Word and as such does not and cannot contradict itself. Scripture thus acts as its own commentary.

A section of the Bible where the meaning is clear can and must be used to interpret a related section of Scripture where the interpretation is less evident or open to several differences of opinion.

These principles of interpretation advocated by Martin Luther and the other Reformers forever changed the course of church history and remain the standard for biblical interpretation for most Protestant churches today.

These two principles of interpreting Scripture in a literal way had another significant long-term impact on the teaching of the church, one that did not appear until well after the time of the Reformers. This later result of interpreting Scripture literally will be the topic of my next article celebrating the 500 year anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation.

Can anyone guess what this future impact might be?

This coming October 31st marks the five hundred year anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. On October 31, 1517 Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in Germany. These 95 Theses became the foundation of the Protestant Reformation, which for many restored the biblical ideal of justification by faith and thereby the purity of the Gospel message.

This coming October 31st marks the five hundred year anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. On October 31, 1517 Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in Germany. These 95 Theses became the foundation of the Protestant Reformation, which for many restored the biblical ideal of justification by faith and thereby the purity of the Gospel message.